David Ball, a mixed-media artist known for his painstakingly constructed surrealist worlds, set himself a challenge: to create 20 complete 24”x36” canvases—double the amount of his last body of work—in half the time it usually takes. One may be inclined to think that by choosing to do so, David had trespassed the line dividing challenge from masochism. But it seems the looming threat of failure is preferable to making—in his view—predictable work.

At the time of this interview David has less than a week to go until the show goes up on the walls of 111 Minna Gallery as part of the three person “Harum Scarum” exhibit. He has no choice but to change, adapt, and let go of his formerly perfectionist ways. I spent time documenting and interviewing David to find out about this new body of work and how setting insane deadlines can be a hell of a way to break old habits.

—Shaun Roberts

At the time of this interview David has less than a week to go until the show goes up on the walls of 111 Minna Gallery as part of the three person “Harum Scarum” exhibit. He has no choice but to change, adapt, and let go of his formerly perfectionist ways. I spent time documenting and interviewing David to find out about this new body of work and how setting insane deadlines can be a hell of a way to break old habits.

—Shaun Roberts

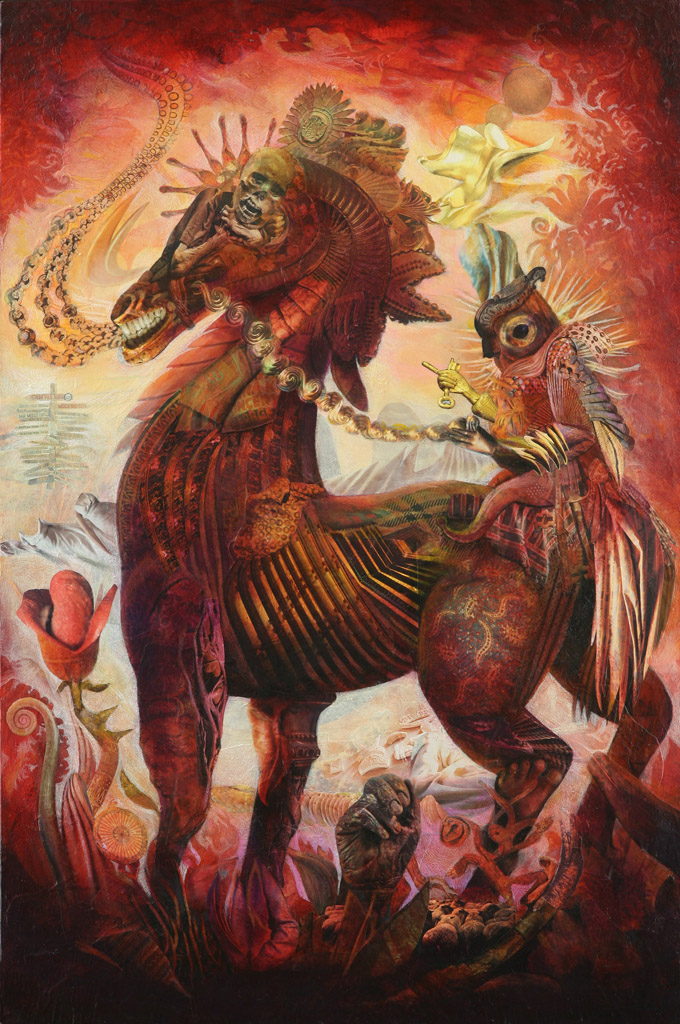

"Conjour" by David Ball

Collage / Mixed media on canvas

24"x36"

Collage / Mixed media on canvas

24"x36"

First off, why the name Harum Scarum? What does that name mean to you?

Harum Scarum to me is kind of being all over the place; coming from many different areas at the same time.

The two other artists in the exhibition; Jesse Balmer, Katherine Brannock and I worked with the gallery on coming up with titles for the show, Harum Scarum was chosen. Out of all the names, Harum Scarum stuck out to me because it seemed most relevant. To be “Harum Scarum” is to be frenetic, and life-wise that was how I was feeling at that time. To have to put so much work together in that timeframe, and to work with so many individual pieces making up those works, I knew my studio would be in complete chaos.

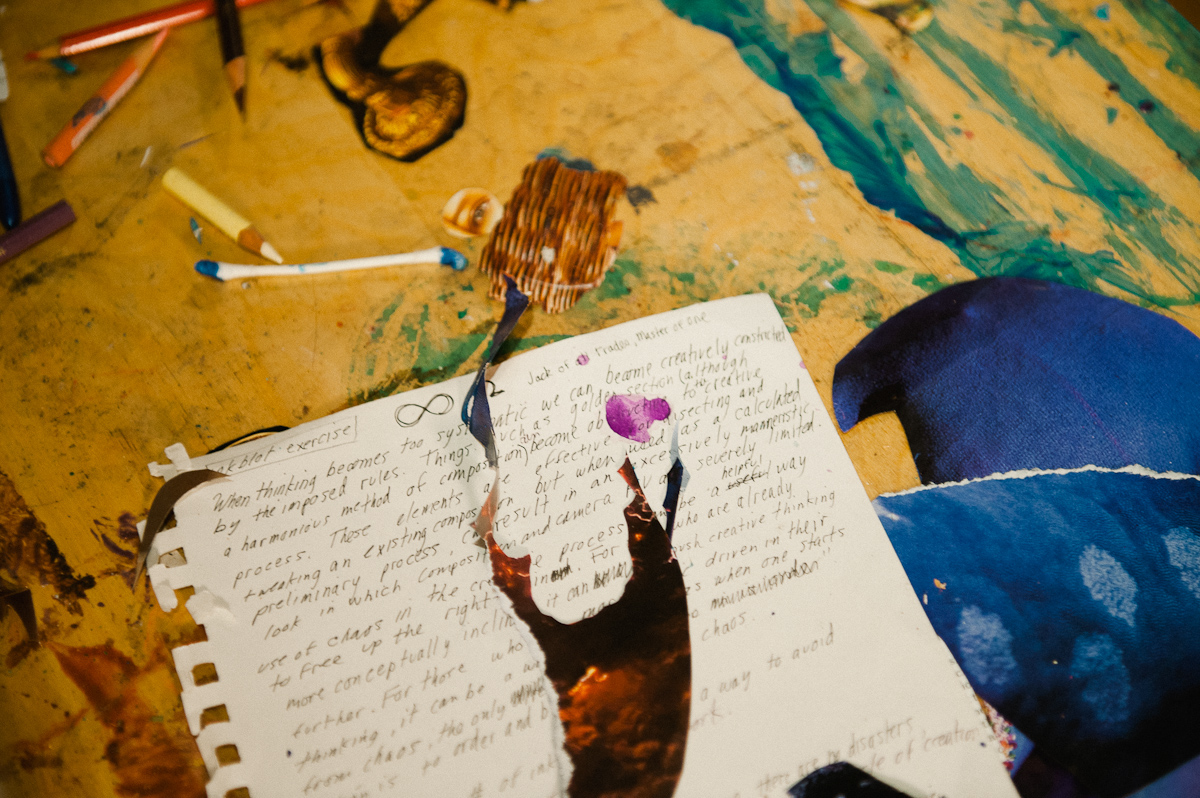

It’s evident in how you lay out all the raw collage elements in the studio, you seem to sift through a hundred little cutout pieces trying to find the one that fits.

I don’t make as good a decision choosing elements for the work when I try to keep everything neat and tidy in the studio. It’s really better to just let it become chaotic and reorganize my space when I’m done.

Harum Scarum to me is kind of being all over the place; coming from many different areas at the same time.

The two other artists in the exhibition; Jesse Balmer, Katherine Brannock and I worked with the gallery on coming up with titles for the show, Harum Scarum was chosen. Out of all the names, Harum Scarum stuck out to me because it seemed most relevant. To be “Harum Scarum” is to be frenetic, and life-wise that was how I was feeling at that time. To have to put so much work together in that timeframe, and to work with so many individual pieces making up those works, I knew my studio would be in complete chaos.

It’s evident in how you lay out all the raw collage elements in the studio, you seem to sift through a hundred little cutout pieces trying to find the one that fits.

I don’t make as good a decision choosing elements for the work when I try to keep everything neat and tidy in the studio. It’s really better to just let it become chaotic and reorganize my space when I’m done.

Are there thematic similarities between your work and the other pieces featured in the Harum Scarum show?

I don’t know if all the work in the show will reflect clear thematic similarities but there’s definitely a chimera quality to the creatures we render. There exists a sort of semi-mythic hallucinatory look to the work and a lot of images of creatures or animals in transition.

I think that everybody brings a different approach to it: Jesse is about really good design sensibility and line work, and Katherine’s character hybrids are really refined using Micron pens. So those techniques combined with my mixed media work will produce a very interesting show because it goes through three very different drafting techniques, certainly from an aesthetic standpoint it was a very smart collection for 111 Minna gallery to put together.

“I wanted to challenge myself to work faster and perhaps even put a little more faith in the process…”

Why did you set yourself this challenge of creating more pieces than ever before in half the time? Is that a reaction to your last body of work?

A little of both, I was very perfectionistic about what I was doing before, I’m using all the exact same materials but it’s the amount in which I use them that makes the difference. I insisted on using tons and tons of pencil on the work last year and it just didn’t make any sense, it reminded me of when another artist friend of mine—David Young V—was working with micron pens. Microns do have an interesting quality but there were times where he was attempting to cover huge areas of space and it just wasn’t practical any more; he could have just as easily filled an area in with an ink brush. Eventually that was exactly what he did and almost instantly his productivity went up because he was moving through things faster. David’s experience inspired me and made me think about trying to find new ways to move more efficiently through my process.

In that sense I wanted to challenge myself to work faster and perhaps even put a little more faith in the process and let whatever came out, come out.

I’m already seeing that happen because conceptually even though there was a loose theme already set to this work, I’m seeing some of the pieces intentions changing as it gets developed. I figure if it’s changing, it’s changing because on some basic level it’s probably the more truthful painting for me to make. I’ll just follow it where it goes.

A little of both, I was very perfectionistic about what I was doing before, I’m using all the exact same materials but it’s the amount in which I use them that makes the difference. I insisted on using tons and tons of pencil on the work last year and it just didn’t make any sense, it reminded me of when another artist friend of mine—David Young V—was working with micron pens. Microns do have an interesting quality but there were times where he was attempting to cover huge areas of space and it just wasn’t practical any more; he could have just as easily filled an area in with an ink brush. Eventually that was exactly what he did and almost instantly his productivity went up because he was moving through things faster. David’s experience inspired me and made me think about trying to find new ways to move more efficiently through my process.

In that sense I wanted to challenge myself to work faster and perhaps even put a little more faith in the process and let whatever came out, come out.

I’m already seeing that happen because conceptually even though there was a loose theme already set to this work, I’m seeing some of the pieces intentions changing as it gets developed. I figure if it’s changing, it’s changing because on some basic level it’s probably the more truthful painting for me to make. I’ll just follow it where it goes.

It seems in one way you’re taking the pressure off of yourself but you’re re-applying the pressure somewhere else.

Yes, the key pressure point is that I have to make more work. Usually there’s a lot of self indulgence in the way I work, I’m used to things taking much longer than they probably should and in this case I can’t have any wasted time.

I’m working on many pieces in parallel now and there are new advantages to it, say I go through a pile of material and I pick up a piece; that piece could potentially satisfy any one of twenty pictures in some capacity. If I was only working on one painting at a time, I would need to search for that one right piece in a pile of thousands over and over again. It would revert me back to this chaotic needle in a haystack search for every single collage element.

I also try not to be systematic anymore, initially I was trying to divide my process into a collage phase, a paint phase and etc.—it doesn’t go that way now, in a day I might do glazing on one thing, few more bits of collage on another, drawing on another and just keep it rotating.

I just really try to take the path of least resistance, keep my energy high, and just keep working and rotating.

Yes, the key pressure point is that I have to make more work. Usually there’s a lot of self indulgence in the way I work, I’m used to things taking much longer than they probably should and in this case I can’t have any wasted time.

I’m working on many pieces in parallel now and there are new advantages to it, say I go through a pile of material and I pick up a piece; that piece could potentially satisfy any one of twenty pictures in some capacity. If I was only working on one painting at a time, I would need to search for that one right piece in a pile of thousands over and over again. It would revert me back to this chaotic needle in a haystack search for every single collage element.

I also try not to be systematic anymore, initially I was trying to divide my process into a collage phase, a paint phase and etc.—it doesn’t go that way now, in a day I might do glazing on one thing, few more bits of collage on another, drawing on another and just keep it rotating.

I just really try to take the path of least resistance, keep my energy high, and just keep working and rotating.

“I figured if you start from chaos, there’s absolute forgiveness.”

So you’re throwing away a lot of the rigidity and dogma from your old process, but are you merely trading them for a different set of rules?

The new rules have yet to be created. But yes, eventually they probably will become a rigid set again. Part of the reason this new process came into existence is my natural inclination to create rules. I would become so rigid in my rule creation I had no room left to breathe, my work became too predictable and I just felt like “ok, I have to do something else”. Whenever I start to know where my work is going I tend to want to begin mixing up the process in order to find a way to make all this “fresher” to me. It’s ongoing challenge to try and transform objects and transform the process itself.

The new rules have yet to be created. But yes, eventually they probably will become a rigid set again. Part of the reason this new process came into existence is my natural inclination to create rules. I would become so rigid in my rule creation I had no room left to breathe, my work became too predictable and I just felt like “ok, I have to do something else”. Whenever I start to know where my work is going I tend to want to begin mixing up the process in order to find a way to make all this “fresher” to me. It’s ongoing challenge to try and transform objects and transform the process itself.

Why do you think you tend to put restrictions down around yourself?

I grew up in a very strict, rule driven household and my dad was an art director for Union Carbide. He was a very well-intended but extremely rigid art director.

I remember spending a month and a half on a stipple piece that was about 16” x 20” when I was in high school; it was absurdly precise, there wasn’t a single dot that touched another dot. When my dad saw it, I think he was actually impressed by it, but his comment was “In a month you’re going to look back on this and think it’s a piece of crap”.

I understand that he was used to holding things to an incredibly high standard, he was hiring artists to do illustrations for him at fifty to sixty thousand dollars a pop and he just didn’t know how to shut it off, but there was something in that comment that I just hated, it was too hard to deal with at 16.

So when I got into college I worked incredibly hard. I immersed myself in an analytical rigid style for a while and just kept on setting up more and more complex tasks for myself. It certainly specialized my intelligence in one way but what I began to realize was that it shut down a different intelligence in me as well; it was becoming hard for me to be imaginative, that’s when I got into Surrealism.

How did surrealism help get you out of the creative rut?

Well I figured if you start from chaos there’s absolute forgiveness. I think of it like walking into a messy room; you can always find ways to make the room more organized than when you entered it, in the same sense when I’m working on a messy painting, it’s not an issue of mistakes, because the entire piece is a mistake in the beginning on some level, all you’re doing from that point on is saving what’s best. I just needed to feel like the pieces were going to take me along for a ride, not having a crystal clear idea of a final destination was refreshing.

So are you not fully aware of the intention of a piece until you think it’s ready to hang?

Within reason, perhaps conceptually yes. My primary figures in this body of work got developed pretty quickly, but subtext and intent don’t really show up until the work is done.

It’s kind of an interesting thing because the work essentially starts out hollow—and I don’t mean that in a bad way—for example: an inkblot is completely hollow, it’s nothing more than just what it is, it is hollow of meaning. But stare at it long enough, your subconscious will try to fill it with meaning and soon enough it can trigger an emotion.

Within reason, perhaps conceptually yes. My primary figures in this body of work got developed pretty quickly, but subtext and intent don’t really show up until the work is done.

It’s kind of an interesting thing because the work essentially starts out hollow—and I don’t mean that in a bad way—for example: an inkblot is completely hollow, it’s nothing more than just what it is, it is hollow of meaning. But stare at it long enough, your subconscious will try to fill it with meaning and soon enough it can trigger an emotion.

Are you trying to grow meaning from arrangements of distinct graphic elements?

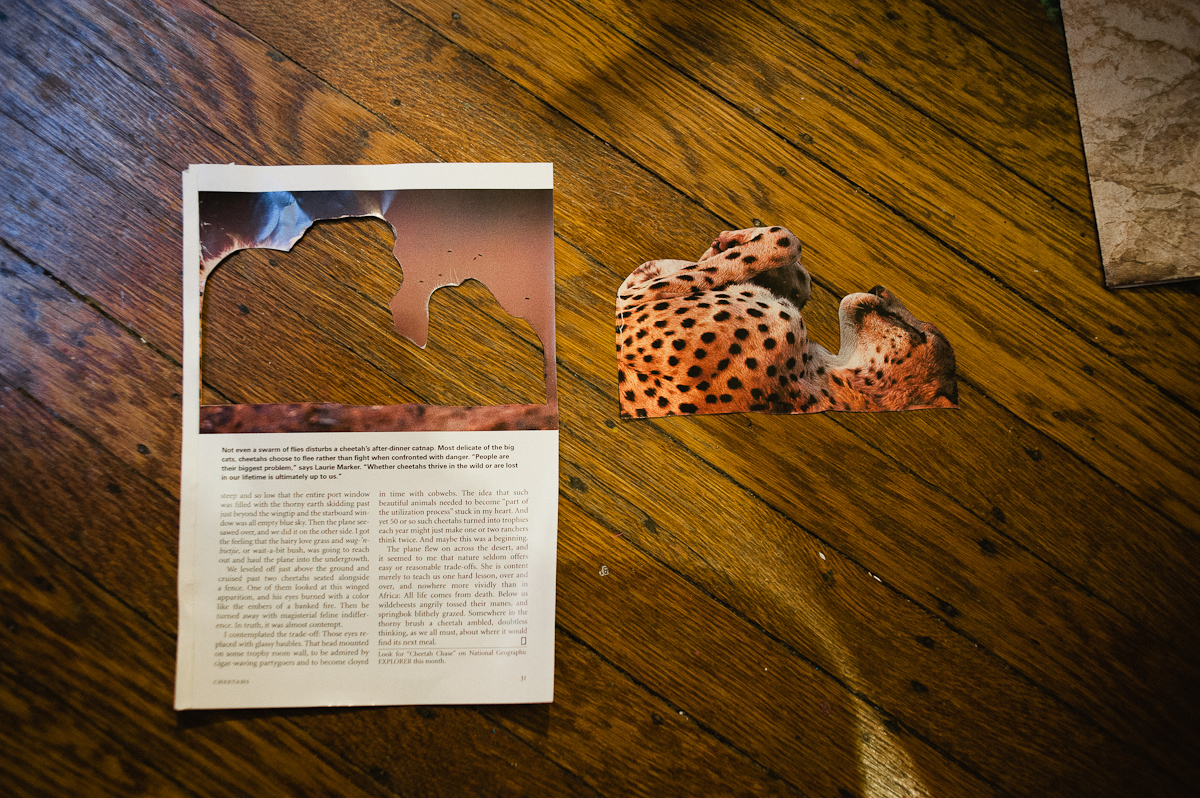

I think the best thing to compare it to is artist Brion Gysin’s cut-up word collages; he was one of pioneers of the technique and then William S. Burroughs went on to develop that process further. But basically Gysin was cutting something out with a blade using a large book as a base. After he was finished he realized he had cut through a bunch of pages and started playing around with the remains, he began slapping these various strips of random words together to see what would happen. The result was this sort of surrealist poetry that was at times, incredibly effective.

What happens is your mind starts to make order from the elements as you remove them from the original context and start rearranging them. They seemingly begin to have purpose and they’ll start to evoke metaphor or speak to some larger idea, it disrupts being trite because the ideas that grow out of the process aren’t obvious.

I think the best thing to compare it to is artist Brion Gysin’s cut-up word collages; he was one of pioneers of the technique and then William S. Burroughs went on to develop that process further. But basically Gysin was cutting something out with a blade using a large book as a base. After he was finished he realized he had cut through a bunch of pages and started playing around with the remains, he began slapping these various strips of random words together to see what would happen. The result was this sort of surrealist poetry that was at times, incredibly effective.

What happens is your mind starts to make order from the elements as you remove them from the original context and start rearranging them. They seemingly begin to have purpose and they’ll start to evoke metaphor or speak to some larger idea, it disrupts being trite because the ideas that grow out of the process aren’t obvious.

So in essence the process gives you a certain scaffolding to begin your work and your subconscious intent will naturally fill that in.

Yes, because the way I see it, people don’t give enough credit to what lingering thoughts already sit with them. Anyone could embark on the surrealist process and arrive at different work. If you’re actually following it, it’s only going to be characteristics of you that come out so there’s no mysterious secret to the process, the process is just a way to facilitate opening things up. The same concepts occur in shamanistic practices like staring at flame; no individual shaman owns the right to the flame, it’s just that the flame evokes something and the process is used again and again. Just like the reading of tea leaves or the spilling of entrails, they’re all divining methods and the earliest forms of Rorschach.

In a way, even someone viewing a finished piece of yours could unlock lingering thoughts and emotions tucked away in their subconscious.

That’s something I find very curious, I do like the discourse between what people choose to see and what not to see in my work. It seems people who want to see darkness will find all the dark components I use to build the piece, people who don’t want to see darkness will see the primary, lighter theme. So yes, it’s your unconscious, subjective point of view that colors how you read the work. I’ve had people who wanted to see a happy picture so badly they’d never see the negative components that make up the characters, but if you’re inclined to get closer you may find cutouts of a bunch of cattle that died in a famine. Of course on the opposite side, I can make use of very positive elements to construct negative characters too.

Yes, because the way I see it, people don’t give enough credit to what lingering thoughts already sit with them. Anyone could embark on the surrealist process and arrive at different work. If you’re actually following it, it’s only going to be characteristics of you that come out so there’s no mysterious secret to the process, the process is just a way to facilitate opening things up. The same concepts occur in shamanistic practices like staring at flame; no individual shaman owns the right to the flame, it’s just that the flame evokes something and the process is used again and again. Just like the reading of tea leaves or the spilling of entrails, they’re all divining methods and the earliest forms of Rorschach.

In a way, even someone viewing a finished piece of yours could unlock lingering thoughts and emotions tucked away in their subconscious.

That’s something I find very curious, I do like the discourse between what people choose to see and what not to see in my work. It seems people who want to see darkness will find all the dark components I use to build the piece, people who don’t want to see darkness will see the primary, lighter theme. So yes, it’s your unconscious, subjective point of view that colors how you read the work. I’ve had people who wanted to see a happy picture so badly they’d never see the negative components that make up the characters, but if you’re inclined to get closer you may find cutouts of a bunch of cattle that died in a famine. Of course on the opposite side, I can make use of very positive elements to construct negative characters too.

"Rest" by David Ball

Collage / Mixed media on canvas

24"x36"

Collage / Mixed media on canvas

24"x36"

“…you need to suspend judgement and see media as resources for art.”

Where do you actually find your source materials?

As far as building components: Goodwills, Salvation Army’s, sometimes used bookstores, there’s this place called Scrap in San Francisco, I think it stands for Scrounger’s Center for Recycled Art Parts— something like that. Since I was a kid I’ve been fascinated with junkyards, charity thrift stores, tag sales, and really anything I could find. I was a little pack rat that would keep little precious treasures.

As far as building components: Goodwills, Salvation Army’s, sometimes used bookstores, there’s this place called Scrap in San Francisco, I think it stands for Scrounger’s Center for Recycled Art Parts— something like that. Since I was a kid I’ve been fascinated with junkyards, charity thrift stores, tag sales, and really anything I could find. I was a little pack rat that would keep little precious treasures.

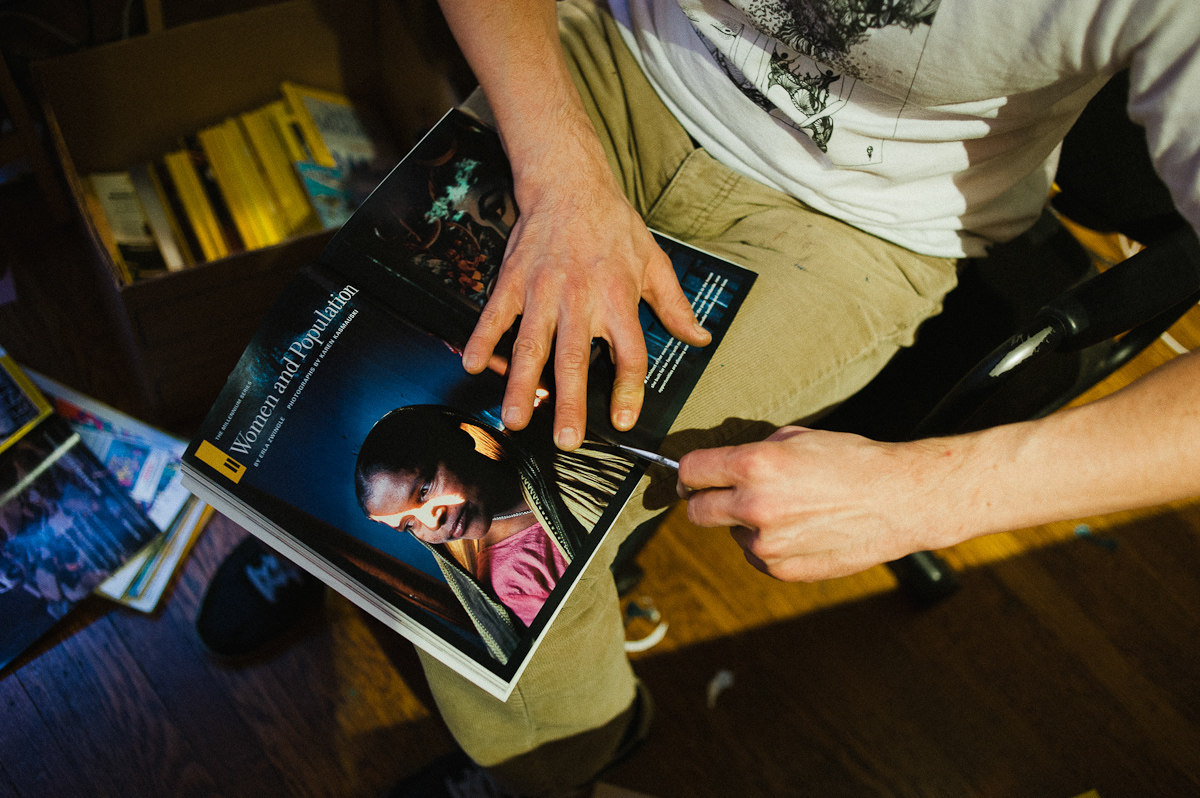

You have a library full of National Geographic magazines at your studio, why that magazine in particular?

For one thing because, none the images are really commercial imagery in the sense of it being photography used to sell merchandise. I try not to really touch that stuff just because, I really feel you’re at risk for copyright problems no matter what you do to transform the image.

I like National Geographic because I like the idea of harvesting imagery from a sense of real life and then reinterpreting it. The magazine is widely read and always has compelling content; everybody seems to have a relationship to it. I also like the idea that someone could be looking at my art with brand new eyes, not even realizing that they might have already seen those elements in a magazine years before.

For one thing because, none the images are really commercial imagery in the sense of it being photography used to sell merchandise. I try not to really touch that stuff just because, I really feel you’re at risk for copyright problems no matter what you do to transform the image.

I like National Geographic because I like the idea of harvesting imagery from a sense of real life and then reinterpreting it. The magazine is widely read and always has compelling content; everybody seems to have a relationship to it. I also like the idea that someone could be looking at my art with brand new eyes, not even realizing that they might have already seen those elements in a magazine years before.

Do you see yourself as a “remixer” in the vein of turntablists and music producers? You seem to share similar processes for your art.

I have a lot of respect for turntablists, I feel that they’re compatriots in collecting. They accrue their own unique collection of raw material through searching and chance—finding Nat Geos at a thrift store is just like a producer digging through crates at a record store, sometimes you find gold, sometimes you don’t.

What I especially like about our process is it requires you to look beyond the superficial, you need to suspend judgement and see media as resources for art; a crude child’s drawing could be judged as drawn incorrectly from a technical point of view but look at it with different eyes and it could possibly evoke some other image in a beautiful way, then everything has potential to be remade.

By suspending judgement you open yourself up to everything. So I feel that even though people may be able to refine their skills in a particular way the more critical they are, they’ll end up losing more than they gain.

I have a lot of respect for turntablists, I feel that they’re compatriots in collecting. They accrue their own unique collection of raw material through searching and chance—finding Nat Geos at a thrift store is just like a producer digging through crates at a record store, sometimes you find gold, sometimes you don’t.

What I especially like about our process is it requires you to look beyond the superficial, you need to suspend judgement and see media as resources for art; a crude child’s drawing could be judged as drawn incorrectly from a technical point of view but look at it with different eyes and it could possibly evoke some other image in a beautiful way, then everything has potential to be remade.

By suspending judgement you open yourself up to everything. So I feel that even though people may be able to refine their skills in a particular way the more critical they are, they’ll end up losing more than they gain.

“It’s akin to what strip mining would do, my process does that to the magazines, they just slowly fall apart.”

So after you acquire these resources, you begin the process of excavating the magazines page by page like a archeologist.

Yeah in that sense they’re like geology maps that show all the different layers of earth sediment and mineral deposits. Pretty much right off the bat I’m already altering it as I take it out of the page, I’m already determining what I want to keep, what I want to throw away. I’ll make palette or textural decisions, I’ll either see that I obviously need a certain shape that turns a certain way in space or my choices will be driven by color or pattern. Each volume contains valuable elements in different strata and it’s a matter of just digging through the pages and bringing them up for resource. It’s akin to what strip mining would do, my process does that to the magazines, they just slowly fall apart.

I was almost going to draw the analogy that you’re also mining your psyche for content in your artwork but hopefully your mind isn’t going to fall apart in the process.

~laughs~ Yeah true. Well we talked about the idea of how psyche plays a role in the work and how I don’t really know the outcome of these until they’re done. In that sense too, most of us don’t know the outcome of what’s going to happen in our life two weeks from now. You might write a schedule for yourself, you might know you have a couple meetings ahead of time but even if you consider schedules, they always change, people make revisions, people make new appointments with you, unexpected events happen…

You get hit by a bus…

You get hit by a bus, break your ankle, break up in a relationship, whatever…all that stuff is always coming at you. There are very few constants in my life and I feel like just the discourse between me and my artwork—whatever madness is going on day to day—I can always make use of here on the canvas. There’s something freeing in that.

Yeah in that sense they’re like geology maps that show all the different layers of earth sediment and mineral deposits. Pretty much right off the bat I’m already altering it as I take it out of the page, I’m already determining what I want to keep, what I want to throw away. I’ll make palette or textural decisions, I’ll either see that I obviously need a certain shape that turns a certain way in space or my choices will be driven by color or pattern. Each volume contains valuable elements in different strata and it’s a matter of just digging through the pages and bringing them up for resource. It’s akin to what strip mining would do, my process does that to the magazines, they just slowly fall apart.

I was almost going to draw the analogy that you’re also mining your psyche for content in your artwork but hopefully your mind isn’t going to fall apart in the process.

~laughs~ Yeah true. Well we talked about the idea of how psyche plays a role in the work and how I don’t really know the outcome of these until they’re done. In that sense too, most of us don’t know the outcome of what’s going to happen in our life two weeks from now. You might write a schedule for yourself, you might know you have a couple meetings ahead of time but even if you consider schedules, they always change, people make revisions, people make new appointments with you, unexpected events happen…

You get hit by a bus…

You get hit by a bus, break your ankle, break up in a relationship, whatever…all that stuff is always coming at you. There are very few constants in my life and I feel like just the discourse between me and my artwork—whatever madness is going on day to day—I can always make use of here on the canvas. There’s something freeing in that.

“Harum Scarum” a three-person exhibition featuring new works by David Ball, Jesse Balmer, and Katherine Brannock. On display February 2–25, 2012 at 111 Minna Gallery, San Francisco, CA

"Flee" by David Ball

Collage / Mixed media on canvas

24"x36"

Collage / Mixed media on canvas

24"x36"